Scores must include:

- A cover page with title, composer’s name, and year of composition.

- An inside page with list of required instruments, duration, and a program note.

- The full name of each instrument to the left of the staff on the first page; subsequent pages should use abbreviated instrument names.

- Bar numbers on the left side of each system, above the top staff and above string staves of orchestral music. Rehearsal letters need not be used in conjunction with bar numbers except in multi-movement works, in which bar numbers restart in each movement but rehearsal letters continue without restarting for the composition’s duration.

Scores must be:

- Legible and prepared to professional standards, with no overlapping or unclear elements. Type-size should be large enough to be read easily by a conductor.

- Printed on letter-sized paper (small-ensemble music) or legal (8.5” x 14”) or tabloid (11” x 17”) paper (orchestral or band music). Set margins so staves are centered on the page and not unreasonably spread out.

- Proofread by a qualified individual other than the composer, who should provide feedback on the music, on instrumental characteristics (balance, ranges and transpositions) and appearance of the score. The same is essential for parts.

- Printed double-sided and bound (spiral or folded/stapled). Music submitted as part of an application (for a competition, graduate school, consideration for performance by an ensemble, etc.) must ALWAYS be professionally bound.

Parts must include:

- Title, composer’s name; instrument name in the top left-hand corner of the first page; instrument name at the top center of all subsequent pages.

- Adequate rests at all page-turns.

- Eight to twelve staves per page, depending on the density of the music.

- Rehearsal letters and/or bar-numbers that match the score. Bar-numbers should appear at the beginning of each staff-system (NOT every five bars, etc.).

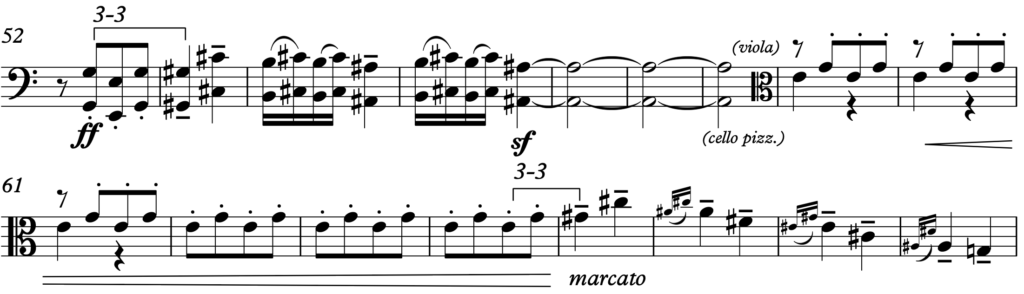

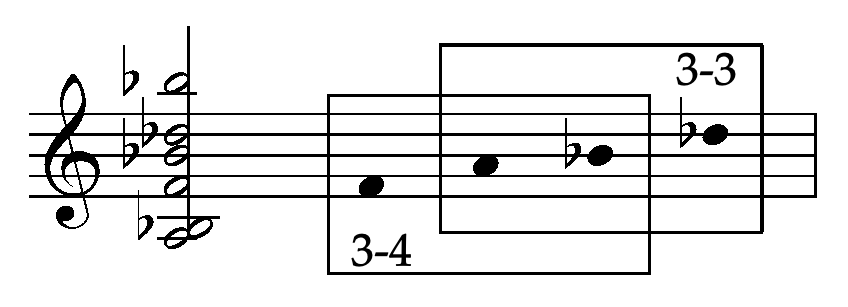

- “H-bar” signs for multiple-bar rests, followed by logical cues to guide performers who rest for several bars. Cues should be musically relevant, audible to the performer being cued, and in the key of the part in which it appears. Cues should appear in small notes above whole-bar rests, and should include the name of the instrument that is performing the passage. It is also convenient to include a bar-number range for the multi-bar rest. For example:

The addition of such cues has been made very easy when using Sibelius software, which includes a “Paste as cue” command.

A special note on cues: cues must appear whenever an instrument rests for more than eight bars. They must appear in parts, but never in the score! Be sure that cue-bars appear with small-note music in the part and bar rests in the score.

Parts must be:

- Legible from the distance of a performer to his or her music stand. The most readable staff size for all instruments is 8.5 mm from bottom staff-line to top.

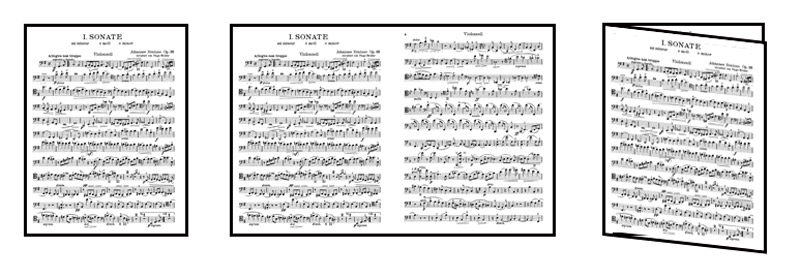

- Not on loose pages: parts may be tape-bound, or printed booklet-style on 11”x 17” paper that is folded in half to form a letter-sized booklet.

- Duplicated according to the required instrumental forces.

- On letter-sized paper* in portrait-format, double-sided. If parts span only two pages, they should be printed next to each other on one side of a portrait-oriented tabloid sheet so that both sides can be read without turning the page. Fold such a part with music facing outward, so the piece can be easily identified in a performer’s folder. Examples (l-r: 1 page, 2 page, and 3+ page parts).

* Professional orchestra and band parts should really be on 10”x 13” paper, but exceptions are made in most situations.

Common Typesetting Mistakes

Tempo markings, rehearsal letters and bar numbers should…

- appear only over the top staff of a score (except in an orchestra, when they also are printed over the violin I staff; they should never appear over each staff.

- appear in each instrumental part.

Dynamic markings should…

- be placed, at minimum, under each instrument’s first note and under the first note of each new phrase that follows a rest of more than a singe bar.

- appear above vocal staves (so not to collide with lyrics)

- reflect the character desired for that instrument’s performance. Only in rare circumstances should dynamics be used to differentiate foreground and accompanimental lines.

- never appear under rests or otherwise empty bars.

Instrument names should…

- not appear the same on two staves. Ex.: when two trumpets have individual lines, the first should be “Trumpet 1 in B♭” and the second should be “Trumpet 2 in B♭” (both should not be “Trumpet in B♭”).

- be abbreviated on subsequent pages for all ensembles larger than quartets (for small ensembles or solos, the names should be omitted).

Staff-systems should…

- be relatively full of music from side to side. If a final system has just one bar, adjust the music to fit it on the previous page or drag the final bar line to narrow the individual bar.

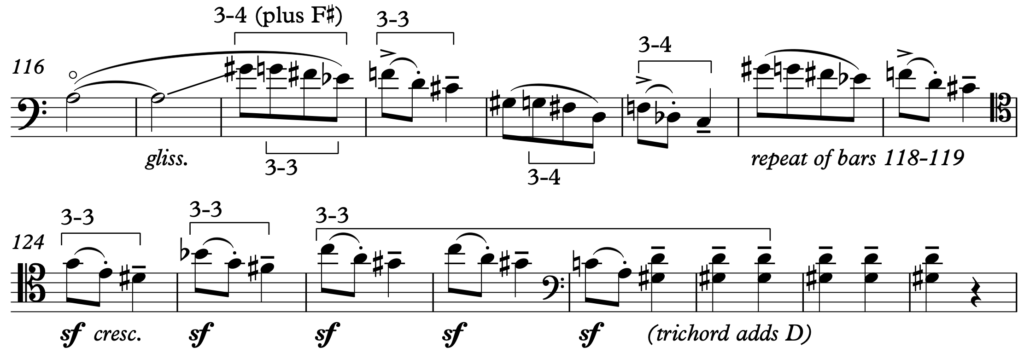

- not just fill the top half of a page:

- For ensembles with five or fewer staves, fit multiple systems in portrait-orientation.

- For ensembles with 5-10 staves, use landscape-orientation and size staves to fill the page from top to bottom. You also may wish to adjust top & bottom margins to center the music on the page.

- For ensembles with more staves, you may wish to use legal-sized paper.

Tempo, technique and expression markings should have appropriate typeface, italicization and capitalization. Common markings in common formats include:

- Principal tempo indications are in bold face, with “sentence capitalization”:

- Adagio, Moderato, Allegro ma non troppo, Tempo I, Fast, etc. Tempo changes are not capitalized:, accel., a tempo, rit., più mosso, etc.

- Some foreign terms are not italicized, while others commonly are (check published scores when in doubt). Less-common terms generally are italicized.

- arco | pizz. | div. | unis. | semplice | dolce | espr. | semplice | crescendo or cresc. (not Crescendo or Cresc. or cres.) | sim.

- Dynamic markings should be printed in bold-faced italics: mp (not mp). On Sibelius, enter these notes as “expression text” (⌘-E), then select from the pull-down menu (control-click) or hold the ⌘ key while typing appropriate letters.

- Don’t capitalize instrumental effects:

- mute on | st. mute | open | sul pont.

Ties and slurs are not the same. In Sibelius, a tie is created on the keypad and a slur is created with the shortcut “S”.

Pick-up bars must have rests of appropriate duration for all instruments that do not play (whole-rests must not be used).